Insights

Keep up to date with industry insights and opinion based articles in the offshore litigation & dispute market. Find out about the work of our expert teams and subscribe to our newsletter.

How are crypto, DAOs and digital assets changing the insolvency and restructuring space?

An exploration of insolvency trends and developments in the crypto, DAOs and digital assets space following a roundtable with Rajah & Tann and the Bak...

The Realities of Crypto Asset Recovery Part 2

The case for independent regulatory remediation and verification

The way an organisation responds to a regulatory crisis is often as important as the crisis itself. A thoughtful, transparent, and expertly led approa...

Employer’s liability for personal injury: Abreu v RS Reinforcements & CNR Construction

Baker & Partners’ Simon Thomas (Partner) and James Wood (Associate) acted in a recent case before the Royal Court clarifying Employer’s liability ...

The First reported wrongful trading case to come before the Royal Court of Jersey

The first reported wrongful trading case to come before the Royal Court of Jersey

Stephen Baker appointed co-chair of the International Bar Association’s Asset Recovery Committee

We congratulate our managing partner Stephen Baker on his appointment as co-chair of the International Bar Association's Asset Recovery Committee.

Digital Asset Recovery and the Unique Challenges posed by DAOs

Never come across the term Decentralised Autonomous Organisation ("DAO") before? You’re not alone, but as of 13 January 2025, these virtual organisa...

Jennifer Colegate is admitted to the bar of the British Virgin Islands

The Realities of Cryptocurrency Asset Recovery

The Guernsey MONEYVAL Report: The conundrum of enforcement versus boosting the economy

Adam Crane welcomed as Fellow by INSOL International at INSOL Hong Kong 2025

Baker & Partners insolvency specialist, Adam Crane to be welcomed as Fellow by INSOL International at INSOL Hong Kong 2025

Hong Kong seminar on Offshore Asset Recovery: Recent developments & best practice

Baker & Partners appoints commercial litigator Fleur O’Driscoll to grow its footprint in offshore disputes in the Asia-Pacific region

Baker & Partners maintains ranking in the 2025 Chambers & Partners Global Guide

"The Baker & Partners team are incredibly responsive and well resourced with great depth." - Chambers & Partners Global Guide 2025

Baker & Partners (BVI) Secures Landmark Ruling Allowing Restoration of a Dissolved BVI Company Beyond the Statutory Limitation Period

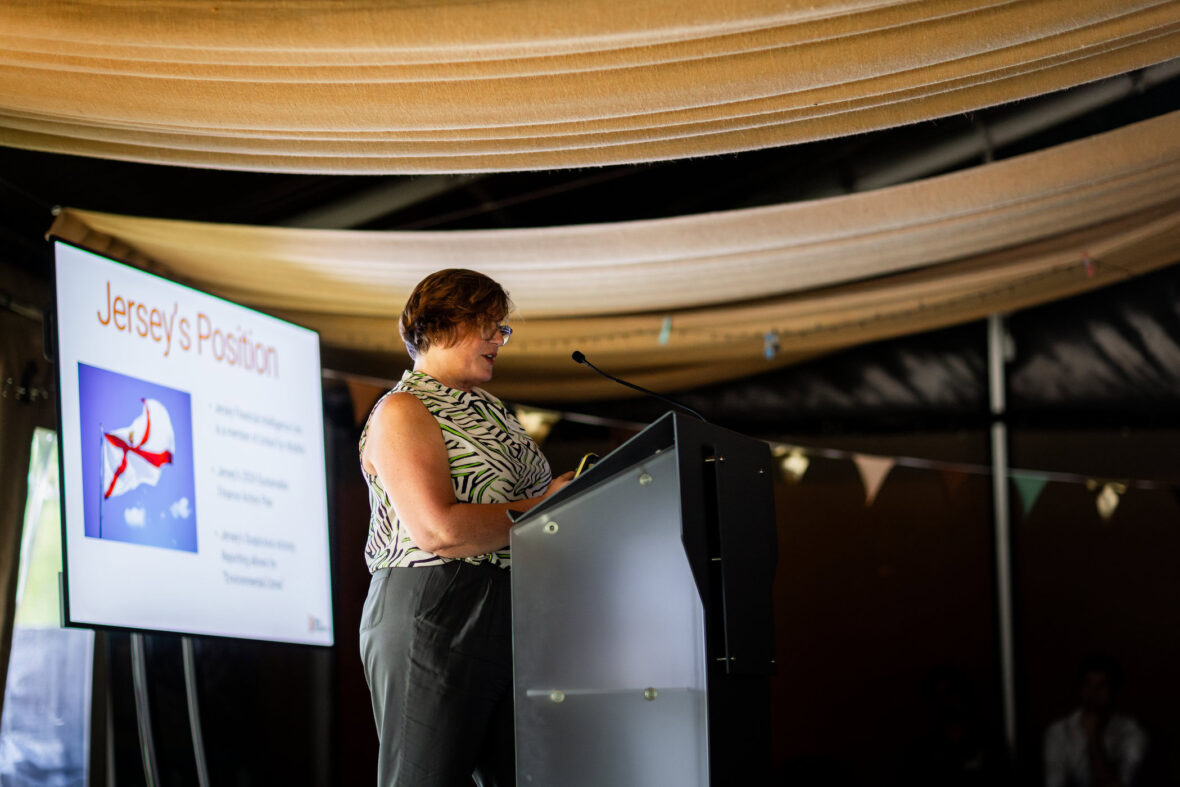

Managing a Regulatory Crisis: All leave is cancelled

Imagine discovering as a newly appointed Non-Executive Director of a financial services business that a series of unfortunate events have snowballed a...

Baker & Partners unravels offshore structure for Dubai bank seeking to enforce non-performing loan

Baker & Partners in Jersey recently obtained orders unwinding a judgment debtor’s transfers of assets into a Jersey trust, because the transfers wer...

Baker & Partners secure the first deferred prosecution agreement in Jersey

Baker & Partners in conjunction with Baker Regulatory Services Limited have successfully negotiated Jersey’s first deferred prosecution agreement fo...

Showing 1-19 of 151